With “One More Orbit”, the pole to pole world circumnavigation speed record for any aircraft has just been broken by an impressive margin! In 46 hours, 39 minutes and 38 seconds, Hamish Harding, chairman of Action Aviation and Gulfstream G650 captain, supported by NASA astronaut Terry Virts and an amazing multinational team in the air and on the ground, managed to beat the previous record, set in 2008 by a Global Express, in a Gulfstream G650ER by 3 hours and 19 minutes! Over a distance of 25,000 miles (40,000 km), the team averaged a speed of 534.97 mph (860.95 km/h) including the refuel stops.

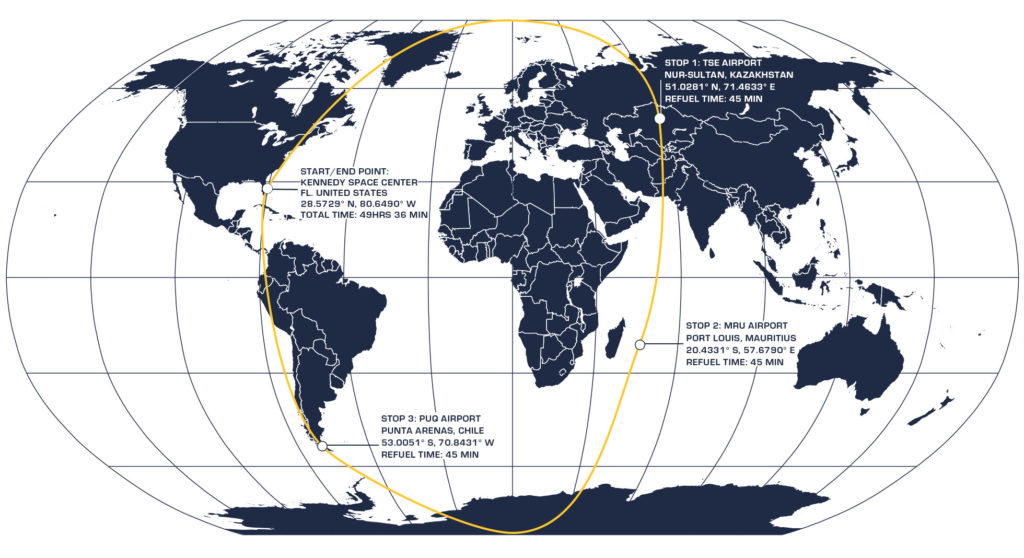

To qualify as an official FAI record, the flight needed to fulfill several criteria. Beginning at a point X (in this case, the Shuttle Landing Facility at Kennedy Space Center in Florida), it was to fly to one of the Earth’s poles, then to the other pole and back to point X. In addition, the equator crossings were required to be separated by 120…180 degrees of latitude and neither the flight crew nor the route were allowed to be changed once the route was declared to the record authorities.

To qualify as an official FAI record, the flight needed to fulfill several criteria. Beginning at a point X (in this case, the Shuttle Landing Facility at Kennedy Space Center in Florida), it was to fly to one of the Earth’s poles, then to the other pole and back to point X. In addition, the equator crossings were required to be separated by 120…180 degrees of latitude and neither the flight crew nor the route were allowed to be changed once the route was declared to the record authorities.

The plan for the record attempt was based on the G650’s “fast cruise TAS” of 500 kt, factored down to an average TAS of 470 kt when considering climb and descent. Expecting an average tailwind of 3 kt and a refuel time (touchdown to takeoff) of 43 minutes, the journey’s average ground speed (from the first takeoff to the last landing) was calculated at 452.5 kt. Compared to the previous world record ground speed of 444.6 kt and considering that speed records must be broken by a margin of at least 1%, this gave the team a time margin of only 22.9 minutes!

The plan for the record attempt was based on the G650’s “fast cruise TAS” of 500 kt, factored down to an average TAS of 470 kt when considering climb and descent. Expecting an average tailwind of 3 kt and a refuel time (touchdown to takeoff) of 43 minutes, the journey’s average ground speed (from the first takeoff to the last landing) was calculated at 452.5 kt. Compared to the previous world record ground speed of 444.6 kt and considering that speed records must be broken by a margin of at least 1%, this gave the team a time margin of only 22.9 minutes!

The 46-hour mission started two days ago at 9:32 EDT (13:32 UTC), the exact time at which Apollo 11 lifted off nearly 50 years ago. The timing underlined the record attempt’s tribute to the past, present and future of space exploration, pushing the boundaries of human ingenuity just like the mission to put a human on the moon half a century ago. Beginning the orbit northbound was much more probable than flying an initial southbound track, but the decision was made on short notice according to the forecast winds.

The 46-hour mission started two days ago at 9:32 EDT (13:32 UTC), the exact time at which Apollo 11 lifted off nearly 50 years ago. The timing underlined the record attempt’s tribute to the past, present and future of space exploration, pushing the boundaries of human ingenuity just like the mission to put a human on the moon half a century ago. Beginning the orbit northbound was much more probable than flying an initial southbound track, but the decision was made on short notice according to the forecast winds.

The first report from Terry Virts came as the flight crossed into Canadian airspace two minutes ahead of schedule. Leaving the dense civilization of North America behind, the plane passed over Hudson Bay on a course straight for the north pole. 1500 miles before reaching it, the crew reported that they were now three minutes behind schedule – significant, considering that the margin to beat the record was only 22 minutes. However, from my experience flying airliners, I knew that most time is lost or gained on the ground. There were possibilities to make up time coming up!

The first report from Terry Virts came as the flight crossed into Canadian airspace two minutes ahead of schedule. Leaving the dense civilization of North America behind, the plane passed over Hudson Bay on a course straight for the north pole. 1500 miles before reaching it, the crew reported that they were now three minutes behind schedule – significant, considering that the margin to beat the record was only 22 minutes. However, from my experience flying airliners, I knew that most time is lost or gained on the ground. There were possibilities to make up time coming up!

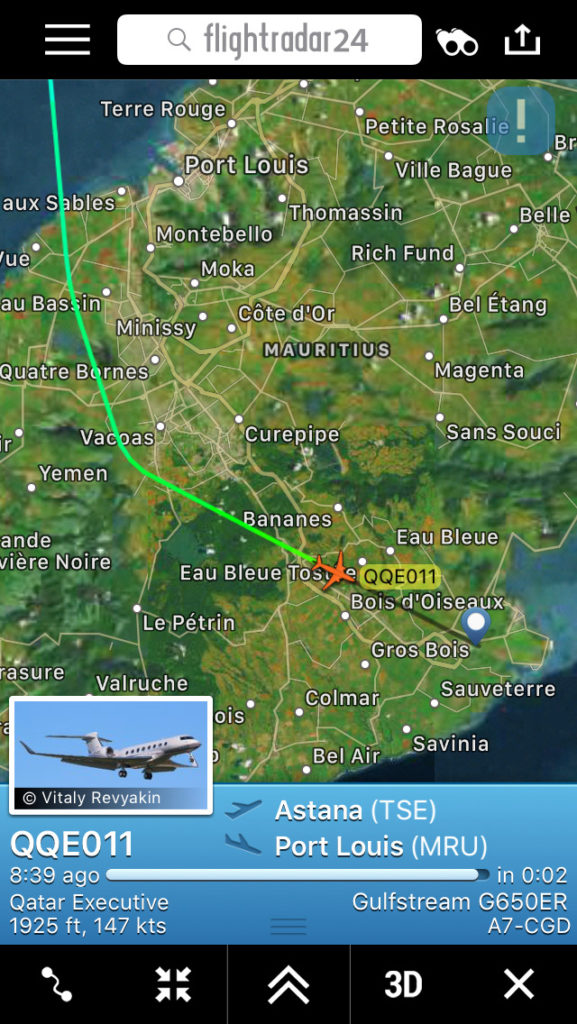

Accompanied by the midnight Sun of the Arctic, the Gulfstream flew over Severny Island and the Kara Sea in northern Russia, passing Surgut and Omsk, cities I’ve come to know from my own flights to the Far East. After 12 hours and 16 minutes, the team reached Nur-Sultan (Astana), 10,770 km away from their point of departure. The fuel stop in Kazachstan was the first of three, all organized like Formula One Grand Prix pit stops. Priority landings and takeoffs were negotiated ahead of time, as the team flew to each location in advance to plan and oversee the process. In Nur-Sultan, another prominent FAI record holder and former crew mate of Virts’ joined the crew. Gennady Padalka, who has spent a total of 879 days in space, supported the endeavor on the sector to Mauritius, which it completed in eight hours and 42 minutes.

Accompanied by the midnight Sun of the Arctic, the Gulfstream flew over Severny Island and the Kara Sea in northern Russia, passing Surgut and Omsk, cities I’ve come to know from my own flights to the Far East. After 12 hours and 16 minutes, the team reached Nur-Sultan (Astana), 10,770 km away from their point of departure. The fuel stop in Kazachstan was the first of three, all organized like Formula One Grand Prix pit stops. Priority landings and takeoffs were negotiated ahead of time, as the team flew to each location in advance to plan and oversee the process. In Nur-Sultan, another prominent FAI record holder and former crew mate of Virts’ joined the crew. Gennady Padalka, who has spent a total of 879 days in space, supported the endeavor on the sector to Mauritius, which it completed in eight hours and 42 minutes.

From the island in the Indian Ocean, the team began the toughest leg from the flight planning perspective: With its very long distance, no diversion possibilities over Antarctica and marginal weather in Chile, it required perfect planning and high vigilance. The jet flew due south, soon seeing the last of the Sun for the next 20 hours as it passed through the polar night. At 75°S latitude, the crew crossed the decision point changing the emergency diversion plan from a direct return to Port Elizabeth (South Africa) to an immediate right turn, abandoning the polar crossing and proceeding directly to a Chilean diversion airfield. Fortunately, all systems continued to operate normally, allowing the flight to continue as planned.

From the island in the Indian Ocean, the team began the toughest leg from the flight planning perspective: With its very long distance, no diversion possibilities over Antarctica and marginal weather in Chile, it required perfect planning and high vigilance. The jet flew due south, soon seeing the last of the Sun for the next 20 hours as it passed through the polar night. At 75°S latitude, the crew crossed the decision point changing the emergency diversion plan from a direct return to Port Elizabeth (South Africa) to an immediate right turn, abandoning the polar crossing and proceeding directly to a Chilean diversion airfield. Fortunately, all systems continued to operate normally, allowing the flight to continue as planned.

Flying right at the edge of the G650’s environmental envelope, the crew needed to descend prior to reaching the south pole to maintain a static air temperature not lower than -80°C. Meanwhile, thanks to the G650’s heated fuel return system, the fuel in the tanks stayed at a comfortable -27°C, well above the freezing point of -40°C for Jet A and -47°C for Jet A1. At 82°S latitude, magnetic headings were lost as expected, the flight continuing with the G650’s advanced avionics on true headings. Crossing the south pole at 20:40 GMT on July 10th, the team probably also set the new north to south pole world speed record!

Flying right at the edge of the G650’s environmental envelope, the crew needed to descend prior to reaching the south pole to maintain a static air temperature not lower than -80°C. Meanwhile, thanks to the G650’s heated fuel return system, the fuel in the tanks stayed at a comfortable -27°C, well above the freezing point of -40°C for Jet A and -47°C for Jet A1. At 82°S latitude, magnetic headings were lost as expected, the flight continuing with the G650’s advanced avionics on true headings. Crossing the south pole at 20:40 GMT on July 10th, the team probably also set the new north to south pole world speed record!

While still flying in total darkness, the crew reached South America and saw the first signs of human civilization since departing Mauritius on the other side of the world thirteen hours earlier. Approaching Punta Arenas, poor visibility and light drizzle were reported in the special weather report at 01:10 UTC, just nine minutes before the G650 landed:

SPECI SCCI 110110Z 08007KT 3000 -DZ BKN003 OVC009 03/03 Q1013 NOSIG=

However, the jet’s enhanced vision system (EVS) supported the pilots in the challenging approach. Using infrared receivers in the nose, it transmits images to the transparent head-up display so well that EVS-trained pilots are allowed to descend to 100 feet (instead of the standard 200′) until a visual reference is established. On this final stop, thirteen hours and 21 minutes after departing from Mauritius, oil service was required on one engine, costing the crew a few precious minutes of time. Still, they were optimistic that they would finish the fourth and final leg on time.

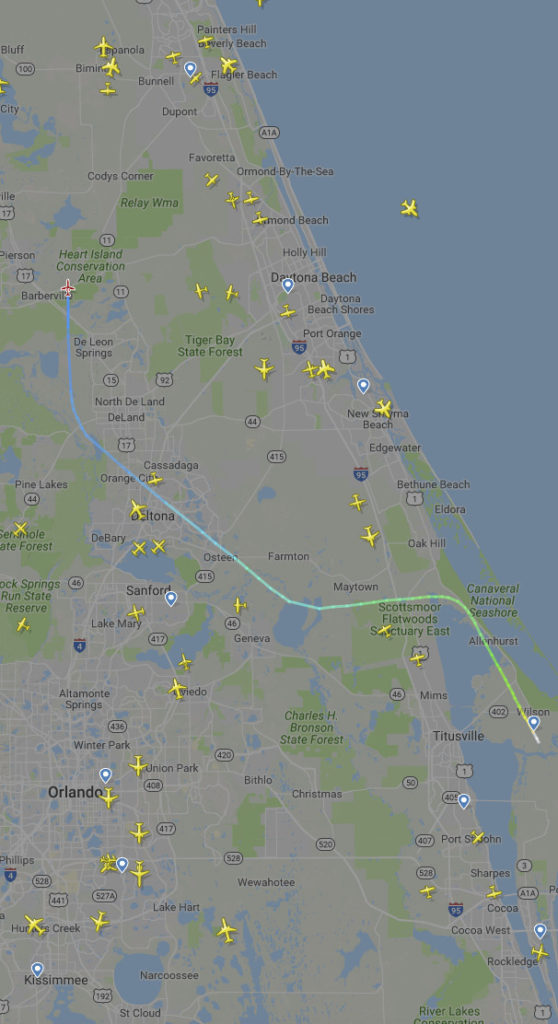

Racing northbound along the coast of Chile, the updated landing time was calculated at 12:15 UTC. A large storm over Columbia forced the pilots to route around the weather at the minimum safe distance while reducing the speed to M0.87 to reduce turbulence stress on the airframe, slowing the flight by another few minutes. But all in all, progress had been better than expected, and heading out over the Caribbean Sea with just two hours to go, the scheduled landing time was now 12:07 UTC!

I wonder how the crew felt as they flew over Cuba, just one hour away from a record-breaking landing. Did they feel a bit invulnerable? Or were they apprehensive, remembering that anything could still happen, just like a good pilot does? Were there signs of target fixation? Were they elated and thinking of the champagne waiting for them or were they going through of every possible hiccup and how they would handle it? I expect they were as professional as they had been for the past two days and even the weeks and months preceding the record attempt that took impressively meticulous planning to accomplish!

I wonder how the crew felt as they flew over Cuba, just one hour away from a record-breaking landing. Did they feel a bit invulnerable? Or were they apprehensive, remembering that anything could still happen, just like a good pilot does? Were there signs of target fixation? Were they elated and thinking of the champagne waiting for them or were they going through of every possible hiccup and how they would handle it? I expect they were as professional as they had been for the past two days and even the weeks and months preceding the record attempt that took impressively meticulous planning to accomplish!

At 12:12 UTC, the G650 landed at the Shuttle Landing Facility less than 47 hours after it departed that same location for its round-the-world flight. The successful pole to pole circumnavigation record attempt is a befitting tribute not only to the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing, but also the 500th anniversary of the first ever global circumnavigation, started in 1519 by Ferdinand Magellan. In five centuries, we’ve reduced the time to navigate around the entire globe from three years to just two days! The documentary that’s being produced about this adventure is sure to be spectacular and I am looking forward to watching it. Congratulations to the entire team of One More Orbit for this legendary feat! You are heroes!

At 12:12 UTC, the G650 landed at the Shuttle Landing Facility less than 47 hours after it departed that same location for its round-the-world flight. The successful pole to pole circumnavigation record attempt is a befitting tribute not only to the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing, but also the 500th anniversary of the first ever global circumnavigation, started in 1519 by Ferdinand Magellan. In five centuries, we’ve reduced the time to navigate around the entire globe from three years to just two days! The documentary that’s being produced about this adventure is sure to be spectacular and I am looking forward to watching it. Congratulations to the entire team of One More Orbit for this legendary feat! You are heroes!

All photos © One More Orbit. This article relies heavily on the following sources: